In his first interview in nearly three years, the legendary singer-songwriter talks about his new disc, ‘Shadows in the Night,’ his love for Frank Sinatra and about life in his 70s

For a man who has lived in the public eye for more than 50 years, Bob Dylan is fiercely private. When he’s not on stage — since 1988, he’s maintained a performance schedule so relentless it’s known as the Never Ending Tour — he slips back into anonymity. But early last summer, Dylan’s representatives reached out and told me he wanted to speak to AARP The Magazine about his new project. “I don’t work at Rolling Stone anymore,” I told them, thinking it was a case of crossed wires, since I put in 20 years there. No, they said, there’s no mistake; he wants to talk to your readers.

And now, after five months of negotiation, a cross-country flight and days of waiting, it is less than an hour until our interview, and I still don’t know exactly where I will meet the reclusive artist. Driving down into the late October sun from the hills of Berkeley, California, toward the San Francisco Bay, I wait for a phone call with directions to a certain floor of a hotel. Then I’ll be given the room number, told to knock, and wait.

We shake hands. Dylan is wearing a close-fitting black-and-white leather jacket that ends at his waist, black jeans and boots. The 73-year-old singer is not wearing his trademark sunglasses, and his blue eyes are startling. We are here to talk about Shadows in the Night, an album of 10 beloved songs from the 1920s to the 1960s. These are not his compositions — they are part of what is often called the Great American Songbook: familiar standards like “Autumn Leaves,” “That Lucky Old Sun” and “Some Enchanted Evening,” along with others, like 1957’s hymnlike “Stay With Me,” that are a bit obscure. In his 36th studio album, Dylan leads a five-piece band including two guitars, bass and pedal steel, and occasional horns, in austere and beautiful arrangements that were recorded live. It is a quiet, moody record with “no heavy drums and no piano,” he says more than once.

As the afternoon deepens, Dylan talks about youth and aging, songwriting, friends and enemies. He recalls with unvarnished affection the performers who shaped his musical DNA, from gospel singer Mavis Staples to rocker Jerry Lee Lewis. Sitting on the edge of a low-slung couch in a dimly lit hotel suite, coiled and fully present — but in good humor — he seems anxious to begin this, his one and only interview for the new album. What follows is condensed and edited from our original conversation and follow-up correspondence.

Bob Dylan takes a surprising turn as a crooner on his newest album, “Shadows in the Night.” — Photo Illustration by Tim O’Brien

Q: Why did you make this record now?

A: Now is the right time. I’ve been thinking about it ever since I heard Willie [Nelson]’s Stardust record in the late 1970s. All through the years, I’ve heard these songs being recorded by other people and I’ve always wanted to do that. And I wondered if anybody else saw it the way I did.

Q: It’s going to be some-thing of a surprise to your traditional fans, don’t you think?

A: Well, they shouldn’t be surprised. There’s a lot of types of songs I’ve sung over the years, and they definitely have heard me sing standards before.

Q: You are very respectful of these melodies — more than you are of your own songs when you perform.

A: I love these songs, and I’m not going to bring any disrespect to them. To trash those songs would be sacrilegious. And we’ve all heard those songs being trashed, and we’re used to it. In some kind of ways you want to right the wrong.

Q: I noticed that Frank Sinatra recorded every one of these songs. Was he on your mind?

A: When you start doing these songs, Frank’s got to be on your mind. Because he is the mountain. That’s the mountain you have to climb, even if you only get part of the way there. And it’s hard to find a song he did not do. He’d be the guy you got to check with. People talk about Frank all the time. He had this ability to get inside of the song in a sort of a conversational way. Frank sang to you — not at you. I never wanted to be a singer that sings at somebody. I’ve always wanted to sing to somebody. I myself never bought any Frank Sinatrarecords back then. But you’d hear him anyway — in a car or a jukebox. Certainly nobody worshipped Sinatra in the ’60s like they did in the ’40s. But he never went away — all those other things that we thought were here to stay, they did go away. But he never did.

Q: Do you think of this album as risky? These songs have fans who will say you can’t touch Frank’s version.

A: Risky? Like walking across a field laced with land mines? Or working in a poison gas factory? There’s nothing risky about making records. Comparing me with Frank Sinatra? You must be joking. To be mentioned in the same breath as him must be some sort of high compliment. As far as touching him goes, nobody touches him. Not me or anyone else.

Q: So what do you think Frank would make of this album?

A: I think first of all he’d be amazed I did these songs with a five-piece band. I think he’d be proud in a certain way.

Q: What other kinds of music did you listen to growing up?

A: Early on, before rock ’n’ roll, I listened to big band music: Harry James, Russ Columbo, Glenn Miller. But up north, at night, you could find these radio stations that played pre-rock ’n’ roll things — country blues. You could hear Jimmy Reed. Then there was a station out of Chicago, played all hillbilly stuff. We also heard the Grand Ole Opry. I heard Hank Williams way early, when he was still alive. One night, I remember listening to the Staple Singers, “Uncloudy Day.” And it was the most mysterious thing I’d ever heard. It was like the fog rolling in. What was that? How do you make that? It just went through me. I managed to get an LP, and I’m like, “Man!” I looked at the cover, and I knew who Mavis was without having to be told. She looked to be about the same age as me. Her singing just knocked me out. This was before folk music had ever entered my life. I was still an aspiring rock ’n’ roller. The descendant, if you will, of the first generation of guys who played rock ’n’ roll — who were thrown down. Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis. They played this type of music that was black and white. Extremely incendiary. Your clothes could catch fire. When I first heard Chuck Berry, I didn’t consider that he was black. I thought he was a white hillbilly. Little did I know, he was a great poet, too. And there must have been some elitist power that had to get rid of all these guys, to strike down rock ’n’ roll for what it was and what it represented — not least of all it being a black-and-white thing.

Q: Do you mean it’s musical race-mixing and that’s what made it dangerous?

A: Racial prejudice has been around awhile, so, yeah. And that was extremely threatening for the city fathers, I would think. When they finally recognized what it was, they had to dismantle it, which they did, starting with payola scandals. The black element was turned into soul music, and the white element was turned into English pop. They separated it. I think of rock ’n’ roll as a combination of country blues and swing band music, not Chicago blues, and modern pop. Real rock ’n’ roll hasn’t existed since when? 1961,1962? Well, it was a part of my DNA, so it never disappeared from me. I just incorporated it into other aspects of what I was doing. I don’t know if this is answering the question. [Laughs.] I can’t remember what the question was.

Q: We were talking about your influences and your crush on Mavis Staples

A: I said to myself, “One day you’ll be standing there with your arm around that girl.” I remember thinking that. Ten years later, there I was — with my arm around her.

Q: Did you recall your original thought?

A: No! [Laughs.] Not until 10 years more beyond that!

Q: Are the songs on this album laid down in the order you would like people to listen to them? Or do you care whether Apple sells them one by one?

A: The business end of the record — it’s none of my business. I sure hope it sells, and I would like people to listen to it. But the way people listen to music has changed, and I hope they get a chance to hear all the songs in one way or another. But! I did record those songs, believe it or not, in that same order that you hear them. We would usually get one song done in three hours. There’s no mixing. That’s just the way it sounded. No dials, nothing enhanced, nothing — that’s it. It’s been done wrong too many other times. I wanted to do it rightly.

Q: You wrote once that a great performer transmits emotion via alchemy. “I’m not feeling this,” you’re saying. “What I’m doing is I’m putting it across.” Is that right?

A: You’re right, but you don’t want to overstate that. It’s different than being an actor, where you call up sources from your own experience that you can apply to whatever Shakespeare drama you’re in. An actor is pretending to be somebody, but a singer isn’t. He’s not hiding behind anything. So a song like “I’m a Fool to Want You” — I know that song. I can sing that song. I’ve felt every word in that song. I mean, I know that song. It’s like I wrote it. It’s easier for me to sing that song than it is to sing “Won’t you come see me, Queen Jane.” At one time that wouldn’t have been so. But now it is. Because “Queen Jane” might be a little bit outdated. But this song is not outdated. It has to do with human emotion. There’s nothing contrived in these songs. There’s not one false word in any of them. They’re eternal.

Q: Do you wish you wrote them?

A: In a way I’m glad I didn’t write any of them. I’m good with songs that I haven’t written, if I like them. I already know how the song goes, so I have more freedom with it.

Q: These songs will have a different audience than they originally had. Do you feel like a musical archaeologist?

A: No. I just like these songs and feel I can connect with them. I would hope people will connect the same way that I do. It would be presumptuous to think these songs are going to find some new audience. The people who first heard these songs are not with us anymore. Besides, when I look out from the stage, I see something different than maybe other performers do.

Q: What are you seeing from the stage?

A: I see a guy dressed up in a suit and tie next to a guy in blue jeans. I see another guy in a sport coat next to another guy wearing a T-shirt. I see women sometimes in evening gowns, and I see punky-looking girls. I can see that there’s a difference in character, and it has nothing to do with age. I went to an Elton John show; there must have been at least three generations of people there. But they were all the same. Even the little kids. They looked just like their grandparents. It was strange. People make a fuss about how many generations follow a certain type of performer. But what does it matter if all the generations are the same?

Q: So we represent people who are 50 and older.

A: Well, a lot of those readers are going to like this record. If it was up to me, I’d give you the records for nothing.

Q: These songs conjure a kind of romantic love that is nearly antique, because there’s no longer much resistance in romance. That sweet, painful pining of the ’40s and ’50s doesn’t exist anymore. Do you think these songs will fall on younger ears as corny?

A: You tell me. I don’t know why they would, but what’s the word “corny” mean exactly? These songs are songs of great virtue. That’s what they are. People’s lives today are filled with vice and the trappings of it. Ambition, greed and selfishness all have to do with vice. Sooner or later, you have to see through it or you don’t survive. We don’t see the people that vice destroys. We just see the glamour of it — everywhere we look, from billboard signs to movies, to newspapers, to magazines. We see the destruction of human life. These songs are anything but that.

Q: What is the best song you’ve ever written about heartbreak and loss?

A: I think “Love Sick” [from 1997’s Time Out of Mind ].

Q: A lot of your newer songs deal with aging. You once said that people don’t retire, they fade away, they run out of steam. And now you’re 73, you’re a great-grandfather.

A: Look, you get older. Passion is a young man’s game. Young people can be passionate. Older people gotta be more wise. I mean, you’re around awhile, you leave certain things to the young. Don’t try to act like you’re young. You could really hurt yourself.

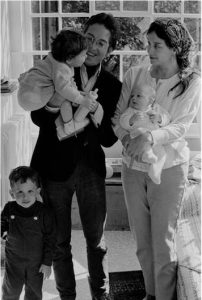

Family man: With wife Sara and kids Jesse, Anna and Sam at home in Woodstock, New York, 1968. — Elliot Landy/Magum

Q: In a period around 1966, you went into seclusion for more than a year, and there was much speculation about your motives. But it was to protect your family, wasn’t it?

A: Totally. That’s right.

Q: I think people didn’t quite want to understand that, because your idiosyncratic view of the world as an artist made them think you were an idiosyncratic person. But you were a typical dad trying to protect his kids.

A: Totally. I gave up my art to do that.

Q: And was that painful?

A: Totally frustrating and painful, of course, because that intuitive gift — which for me went musically — had carried me so far. I did do that, yeah, and it hurt to have to do it. But I didn’t have a choice.

Q: Your life is largely spent on the road: 100 nights a year. I read that your grandmother once told you that happiness is not the road to anything. She said it is the road.

A: My grandmother was a wonderful lady.

Q: You obviously get great joy and connection from the people who come to see you.

A: It’s not unlike a sportsman who’s on the road a lot. Roger Federer, the tennis player, he’s working most of the year. Like maybe 250 days a year. I think that’s more than B.B. King does. So it’s relative. I mean, yeah, you must go where the people are. But happiness — are we talking about happiness?

Q: Yeah.

A: OK, a lot of people say there is no happiness in this life and certainly there’s no permanent happiness. But self-sufficiency creates happiness. Just because you’re satisfied one moment — saying yes, it’s a good meal, makes me happy — well, that’s not going to necessarily be true the next hour. Life has its ups and downs, and time has to be your partner, you know? Really, time is your soul mate. I’m not exactly sure what happiness even means, to tell you the truth. I don’t know if I personally could define it.

Q: Have you touched it?

A: Well, we all do.

Q: Held it?

A: We all do at certain points, but it’s like water — it slips through your hands. As long as there’s suffering, you can only be so happy. How can a person be happy if he has misfortune? Some wealthy billionaire who can buy 30 cars and maybe buy a sports team, is that guy happy? What then would make him happier? Does it make him happy giving his money away to foreign countries? Is there more contentment in that than in giving it here to the inner cities and creating jobs? The government’s not going to create jobs. It doesn’t have to. People have to create jobs, and these big billionaires are the ones who can do it We don’t see that happening. We see crime and inner cities exploding with people who have nothing to do, turning to drink and drugs. They could all have work created for them by all these hotshot billionaires. For sure that would create lot of happiness. Now, I’m not saying they have to — I’m not talking about communism — but what do they do with their money? Do they use it in virtuous ways?

Q: So they should be moving their focus here instead of …

A: Well, I think they should, yeah, because there are a lot of things that are wrong in America, and especially in the inner cities, that they could solve. Those are dangerous grounds, and they don’t have to be. There are good people there, but they’ve been oppressed by lack of work. Those people can all be working at something. These multibillionaires can create industries right here in America. But no one can tell them what to do. God’s got to lead them.

Q: And productive work is a kind of salvation in your view? To feel pride in what you do?

A: Absolutely.

Q: You’ve been generous to take up all of these questions this afternoon.

A: I found the questions really interesting. The last time I did an interview, the guy wanted to know about everything except the music. People have been doing that to me since the ’60s — they ask questions like they would ask a medical doctor or a psychiatrist or a professor or a politician. Why? Why are you asking me these things?

Q: What do you ask a musician about?

A: Music! Exactly.