By Geoff Stanton From the Barrel House

Every desk tells a story. Take a look at your own. It may be the only place you can keep ordered; a solitary cove where you can wind life back, expand the surface and skim like a stone. But whether it’s via a hatch, a cup of tea, a bottle of whiskey, four walls of chaos and a nap – the desk is a great helm. Here’s a classical tour of some of the big guys; their desks, methods, modes for writing the masterpiece that will keep the ghost lingering.

Dalton Trumbo gets down to work, Mitzi Trumbo/AP Images

Hollywood heavyweight and screenwriting legend Dalton Trumbo. He did most of his writing sitting in the tub, working on a tray suspended over suds. According to his wife, he’d spend days in the bathroom, writing, soaking and smoking – Kirk Douglas remarked that Trumbo sometimes smoked up to six packs of cigarettes a day.

The picture comfort is instructive; next time you’re wasting time in a bath, remember it was here Trumbo wrote films such as The Sandpiper (1965) for Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, The Horsemen (1971) for director John Frankenheimer and his last film, Papillon (1973). And all that after he was blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1950 – during which time he focused his skills on letter writing. Although he did posthumously win an Academy Award for secretly writing Roman Holiday (1953).

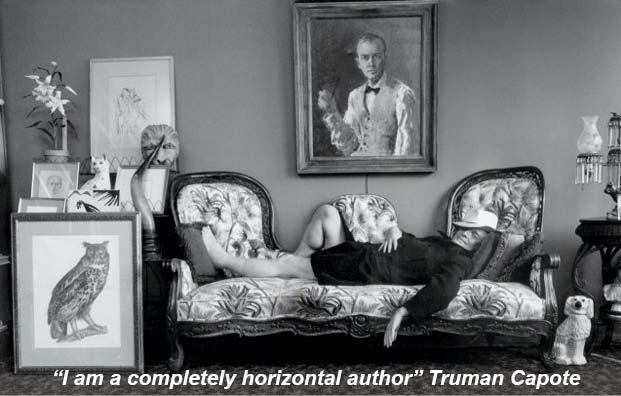

Truman Capote and his big ideas, 1977, Arnold Newman.

Inspiration. A glass of sherry in one hand and a pencil in another. “I am a completely horizontal author” Truman Capote told the Paris Review in 1957. “I can’t think unless I’m lying down, either in bed or stretched on a couch and with a cigarette and coffee handy. I’ve got to be puffing and sipping. As the afternoon wears on, I shift from coffee to mint tea to sherry to martinis. No, I don’t use a typewriter. Not in the beginning. I write my first version in longhand (pencil). Then I do a complete revision, also in longhand.”

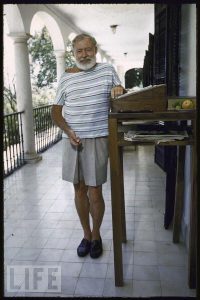

Ernest Hemingway at the Standing Desk on the Balcony of Bill Davis’s home near Malaga, Life/Time Images.

Hemingway wrote 500 words a day – mostly in the mornings to avoid the heat. A prolific writer, he also knew when to stop. In a letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1934, he wrote, “I write one page of masterpiece to ninety-one pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

Hemingway discovered the standing desk method from his editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons, Maxwell Perkins, after an injury prevented him from spending prolonged amounts of time sitting down. In the 18th and 19th centuries, nearly everyone used a standing desk. AE Hotchner recalls Hemingway’s home set-up in Havana, in Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir:

“In Ernest’s room there was a large desk covered with stacks of letters, magazines, and newspaper clippings, a small sack of carnivores’ teeth, two unwound clocks, shoehorns, an unfilled pen in an onyx holder, a wood carved zebra, wart hog, rhino and lion in single file, and a wide-assortment of souvenirs, mementos and good luck charms. He never worked at the desk. Instead, he used a stand up work place he had fashioned out of a bookcase near his bed. His portable typewriter was snugged in there and papers were spread along the top of the bookcase on either side of it. He used a reading board for longhand writing.”

“Ducking for apples” said Dorothy Parker. “Change one letter and it’s the story of my life.” Dorothy Parker; American poet, short story writer, critic, satirist – and yet another blacklisted name during the 1950s. In her day she was known as a ‘wisecracker‘ – a label that may have been applied to Oscar Wilde had he been born in New Jersey – but one Parker despised. Yet her literary output and reputation for sharp wit has endured.

Dorothy Parker in the midst of writer’s block. She sent this telegram to her editor, Pascal Covici, as she couldn’t bring herself to look him “in the voice.”

Asked by a journalist during an interview, “Where’s the best place to write?” Parker replied, “In your head.” And her head was clocked in constantly, from speakeasies through three marriages (two to the same man – “I put all my eggs in one bastard”), the heavy drinking and smoking and some unhappiness. But her style and wit continue to entertain readers. “I’d like to have money. And I’d like to be a good writer. These two can come together, and I hope they will, but if that’s too adorable, I’d rather have money.”

Nearly finished? Lost in spools. The draft of Jack Kerouac’s Beat-defining phenomenon ‘On the Road’ appeared to the world in April 1951 as a single 36 metre (120-foot) role of paper.

Fueled by the same fever as his characters, Jack Kerouac racked a word-count to help him set course for a complete novel. “That’s not writing” Capote famously remarked,”that’s typing”. But when the whiskey and malt loosened its grip, habits at the Kerouac table-top were disciplined. From the time of first novel The Town and the City Kerouac kept a log; between 1,000 to 5,000 words a night.He also created a formula to mimic the ‘batting average’. The goal was a .400 batting average – on par with Ted Williams.

Kerouac’s fierce verbal also invoked a set of commandments, tacked on the wall of Allen Ginsberg’s hotel room in North Beach a year before Ginsberg published Howl.

“Scribbled secret notebooks, and wild typewritten pages, for yr own joy. Submissive to everything, open, listening. Try never get drunk outside yr own house. Be in love with yr life. Accept loss forever. Believe in the holy contour of life. Struggle to sketch the flow that already exists intact in mind. Don’t think of words when you stop but to see picture better”

After hours. Jack Kerouac, Lucien Carr, Allen Ginsber, 1959. Image John Cohen/Hulton Archive

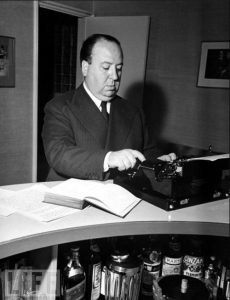

Alfred Hitchcock with his 1930’s Black Underwood typewriter – and cocktail bar. “More work was done on the script in the evening over cocktails, than any other time” said collaborator Charles Bennett. Life/Time images.

“In the morning, I used to get up and pick up Hitch in Cromwell Road, where he lived, at ten o’clock exactly” says screenwriter Charles Bennett, who collaborated with Hitchcock from his earliest ‘talkies’ – including The Man Who Knew Too Much in 1934 – establishing the innovative wit, freshness and originality Hitchcock subsequently demanded of his writers. “He would be sitting on the curb waiting for me. And then we would go to the studio where we would discuss the script and what I was doing with it”.

“Then at about one o’clock, everything would stop, and we’d go to lunch, always at the Mayfair Hotel, and have a wonderful lunch. Then come back and at that point, Hitch would usually go to sleep in the office, and I would do a little work, and possibly doze off too slightly. At about five o’clock, we would go back to Hitchcock’s flat where we would start having nice cocktails for the evening, and talk more and more and more about the script. And I think more work was done on the script in the evening over cocktails, than any other time.”

Tennessee Williams faces a terrible question, Life/Time images

“I write as soon as I get up in the morning – facing that terrible question as soon as possible. Some mornings I get up and what I’ve been working on is repugnant to me. So then I shift to some other thing I’ve been working on. I find it absolutely necessary to have two things going on at once, then I can shift back and forth” (Tennessee Williams interview with John Gruen, 1965)

William Faulkner, 1943. “My own experience has been that the tools I need for my trade are paper, tobacco, food, and a little whiskey. Life/ Time images.

“I can’t write if someone else is in the house, not even the cleaning woman” said Patricia Highsmith, Tom Ripley creator, and bringer of many other thrillers – including Hitchcock’s ‘Stranger’s on a Train’.”I have Graham Greene’s telephone number, but I wouldn’t dream of using it. I don’t seek out writers because we all want to be alone.”

Roald Dahl in his writing hut.

Roald Dahl created space the same way his mind burrowed out a giant peach; fantastically. He believed a writing space should be highly personal. His writing hut was closed to everyone, including family. A wing-back chair hollowed out to comfort a bad back, a writing board made from wood and green baize fitted across the arms. An electric heater hung directly overhead.

The hut was also decked with curios and artifacts; a piece of his own hip bone, his own preserved spinal shavings, fossils, magazines, fan letters, old photos, family totems, bookmarks drawn specially for him by friend and illustrator Quentin Blake (he only ever seen the interior once) and an enormous ball of wrapper foil slow-built from years of lunching on Cadbury’s chocolate.

Now that the great writing chair is empty you can take an interactive tour of the hut.

“As things stand now, I am going to be a writer. I’m not sure that I’m going to be a good one or even a self-supporting one, but until the dark thumb of fate presses me to the dust and says ‘you are nothing’, I will be a writer.”, Hunter S Thompson.

Hunter S. Thompson is best known for writing in a spin of campaign trails, Hell’s Angels, Holiday Inns, Wild Turkey, mescalin and an occasional lawyer. But while attending Columbia University School of General Studies and taking creative writing, he also worked at Time for $51 a week as a copy boy. During this stint he would sneak off into a room with a typewriter and rewrite his favorite author’s books, including F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gastby and Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, before moving on.

As far as I’m concerned, it’s a damned shame that a field as potentially dynamic and vital as journalism should be overrun with dullards, bums, and hacks, hag-ridden with myopia, apathy, and complacence, and generally stuck in a bog of stagnant mediocrity. If this is what you’re trying to get The Sun away from, then I think I’d like to work for you. (Thompson’s Cover letter to Vancouver Sun, looking for a job, 1957)

Henry Miller in his office

Human song-sheaf Nick Cave has replaced harmful addictions with work since the eighties, and implies as much himself: “Writing is a necessary thing for me, just to keep myself level. It has beneficial effects on my life”. When he bunked down in Berlin to write the And the Ass Saw The Angel, it seemed his method was not so different from songwriting – or taking drugs. “I write a lot, and very often I write a couple of lines that are particularly revealing in some kind of way. And then as a few more lines get added and a piece gets added, eventually the song pretty much takes over and you can’t really find a way to change those things.”And isn’t that what it’s all about?

“More Things to Remember…”, Nick Cave, Melbourne Arts Centre

Published with permission from Geoff Stanton From the Barrel House