WHY THE WORLD OF SCIENCE OWES A MAJOR DEBT TO OUR ORIGINAL INDIGENOUS ZOOLOGISTS

JOHN McNAMEE REPORTS

A major new book has chronicled for the first time the significant contribution Australia’s indigenous population made to the great zoological discoveries in the early days of settlement.

The work describes in detail how the early explorers, botanists and zoologists relied heavily on the native tribes to guide them over inhospitable terrain and gain access to the vast wealth of Australia’s unique native fauna.

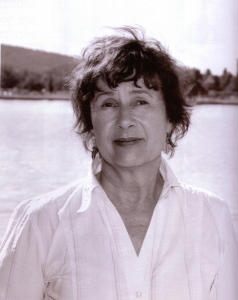

Co-authored by research academics and historians Professor Penny Olsen and Lynette Russell, Australia’s First Naturalists … Indigenous Peoples’ Contribution to Early Zoology, outlines in detail the previously unrecognised complex knowledge of indigenous societies.

“The 19th century in particular was a great era of naturalist studies and findings and it was thanks to the cooperation between the indigenous peoples and the European settlers that the world got to know about our iconic animals such as the koala, the echidna, the platypus and the superb lyrebird,” Penny Olsen told Go55s.

“There had previously been many books written about the geographical and botanical findings, such as those of Sir Joseph Banks, but there wasn’t much history of the zoological connection,” she said.

“Most of the fauna discovered was unique to Australia, nobody had seen anything like them, and of course when the first platypus skin was sent to the UK, everyone thought it was a hoax.

“It was using the vast knowledge of the local tribes that the European settlers could collect and identify the various species such as the egg-laying mammals,” she said.

The beautifully illustrated book describes how over the millennia the indigenous populations had refined their hunting skills including the use of fire to round up kangaroos in their battle for survival.

“The indigenous peoples could understand the life cycles of the animals and the seasons, and they knew where to look for such things as swans eggs, or set up fish traps, or smoke out animals from trees or underground burrows,“ she said.

“Some of the fauna were nocturnal and the zoologists needed that expert knowledge of where to go to collect the various species.

“The indigenous people had some remarkable hunting tactics, for example they could tag bees and then follow them back to their hives, they could convert termite mounds into ovens and use feathered sticks to lure emus into traps.

“It was all this type of knowledge that made that era of naturalist discovery here in Australia so significant,” she said.

“But it wasn’t just the animals or the plants, explorers such as Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson made many unsuccessful attempts to explore a path through the Blue Mountains, but it was only when they had indigenous guides that they were able to make their historic crossing.”

Generally, the book finds that the relationship between the native peoples and the settlers in cooperating in these biological studies was friendly as the indigenous tribes were not only hunters but traders as well.

“Of course there were many cases of abuse and violence between the parties, but in a lot of the cases the young man of the tribes in particular liked to show off their skills and lead the naturalists to otherwise hidden animal locations,” Penny said.

“A classic case would be that of Prussian-German settler William Blandowski and his association with the Nyeri Nyeri peoples of the Murray-Darling junction in the mid-1850s.

“He hired the whole Nyeri tribe to hunt out hitherto unknown specimens for him one of which is the now extinct pig-tailed bandicoot,” she said.

In the book Blandowski is quoted as writing that the Nyeri people had collected 24 species, five of them entirely new to science: “Most of these quadrupeds I have collected in large numbers and they are entirely the results of my friends the Yaree Yaree (Nyeri) Aborigines and for which I have given them flour, sugar, tea, blankets, clothing and other small presents amounting in all to about 200 pounds in value”.

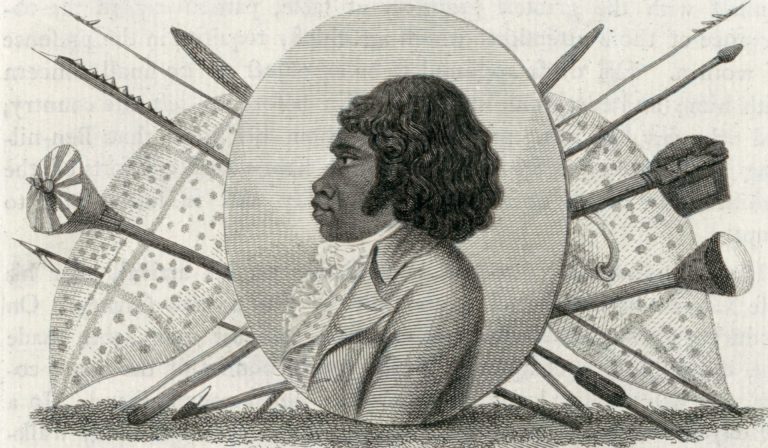

Many individual Aborigines established firm relationships with explorers and naturalists including one of the earliest, Bennelong (Eora name Wolarewarre) from the Wangal clan on the southern side of the Parramatta River in Sydney who shared his knowledge with the First Fleet officers.

There was also an Awabakal man called Desmond who in the 1820s assisted Lieutenant William Coke, a Deputy Commandment in Newcastle and a keen taxidermist in collecting rare bird species which he then sent home to relatives in England.

Desmond also brought Coke and his party fish, ducks, pigeons, kangaroos and wallabies for fresh food but he was later severely wounded in an intertribal conflict.

“Of course, unfortunately a lot of the payments to the Aborigines would also have been in alcohol and we know what devastating and long-lasting results that has had, “Penny said.

“And another downside would have been the over-hunting of many species which led to them becoming extinct.”

The book explains further: “Indigenous Australians valued animals not only for their use, but also for their symbolism and interconnection with the ancestral realm and the entire living system, humans included. ….. For many Aboriginal people some of the animals in their country were regarded as non-human people, kin and clan members.

“They perceived that animals either shared the same qualities as themselves or were distinguished by not possessing those characteristics….”

The book goes on: “Late 18th to early 19th century European scientists were obsessed with describing and classifying the natural world in a way that required a world view and a standard rationale and methodology….It was considered quite a prize to discover, name and describe a species that was new to science and identify its place in the great pantheon of creatures….

“In order for indigenous people to survive and thrive over the millennia, ecological, environmental and zoological knowledge would have been required .. in the absence of broadscale farming…

“They altered waterways to manage fish and others cultivated tubers such as yams and grains such as native millet…

“These land management strategies were designed to enhance certain plants and animals to assist their procurement…Aboriginal Australians may not have had domesticated animals but what they did, in effect, was to domesticate the landscapes.”

It is a fitting tribute to the authors of this important book the world can at last acknowledge the enormous contribution of our indigenous peoples to the fields of science.

*Australia’s First Naturalists .. Indigenous Peoples’ Contributions to Early Zoology…..by Penny Olsen and Lynette Russell. NLA Publishing. Available now. RRP $44.99.

AUTHOR PICS

Penny Olsen is an Honorary Professor in the Division of Ecology, Evolution and Genetics at the Australian National University and has written extensively for the National Library of Australia.

Lynette Russell is a Professor at the Centre for Australian Indigenous Studies, Monash University and has wide-ranging experience of Aboriginal peoples and anthropology.

Main Picture: Bennelong…one of the earliest Indigenous Australians to share his natural history knowledge with the First Fleet.