The passing of Richie Benaud, the former Australian cricket captain and long-time television commentator in Britain and his native Australia, recalls an era in broadcasting when a voice became synonymous with a sport. For many, like me, who grew up watching cricket on BBC television, Benaud’s crisp Aussie accent delivered incisive and often wry analysis of the game of cricket.

Benaud grew up in New South Wales during the great depression of the early 1930’s. Cricket was a natural distraction for many young Australians and Don Bradman was the most captivating player of the age. Taught how to bowl as a youngster by his father Lou, Benaud made his debut in the Sheffield Shield in 1949 and received his first “Baggy Green” cap for Australia against the West Indies in January 1952.

Benaud’s record as an all-round cricketer would have been enough to ensure his status as one of Australia’s all-time greats and as captain he revitalised Australian cricket in the early-1960s. But he was as courageous in life as he was on the field, and in 1959 took the previously unprecedented step of signing up for a broadcasting training course at the BBC while still at the peak of his powers as a professional sportsman.

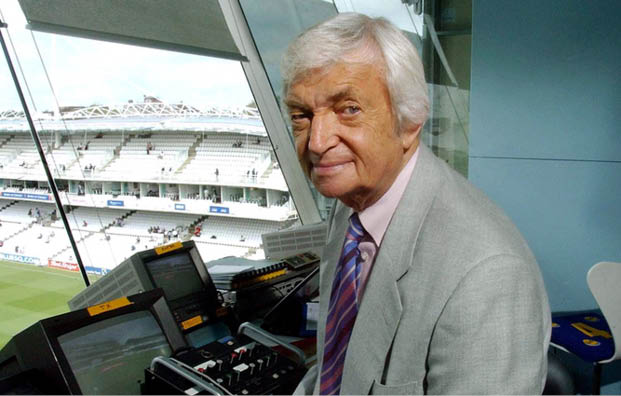

When the BBC’s head of sport, Bryan Cowgill, offered him a role in the commentary box in 1964 he became, arguably, the first of a generation of commentators to successfully make the leap from performing in front of the camera to the principal communicator behind one. Others, such as English test cricketer Denis Compton, had taken on the role as summariser, but Benaud was the main voice people heard in their living rooms.

In interviews and his autobiographies, Benaud always paid homage to some of the pioneering television commentators of the 1950’s including Henry Longhurst (golf), Dan Maskell (tennis) and Peter O’Sullivan (horse racing). Both Longhurst and Maskell had the unerring skill to know when to be silent, and O’Sullivan was imperious in his preparation and knowledge of the event he was covering.

Perfect timing

Benaud combined both skills with alacrity. Unlike radio, where silence in the commentary box is a major faux pas, in television sport knowing when to shut up and let the picture tell the story remains the most valued attribute of the commentator on top of their game. Having played at the highest level, Benaud’s understanding of the rhythms of cricket, particularly in its longer test format, gave him invaluable instinct for knowing when to speak and to avoid saying the obvious.

His style of commentary seemed in keeping with the flow of the game itself, so long silences would be followed by what Peter Wilby of The Observer once called a “referential whisper” annotating the broader narrative of what was happening on screen.

My own abiding memories of Benaud’s commentaries were that he always sounded relaxed, like imparting pearls of wisdom to a close friend. There was a sense that he knew what the viewer expected to hear or know about a particular situation.

Such down-to-earth communication skills masked a more complex production process of modern televised sport. Over Benaud’s lifespan as a commentator this involved a multitude of innovations in the use of cameras (including those inserted in the stumps), action slow-motion replays, statistical overlays, hawk-eye and numerous other forms of technological wizardry. Benaud managed to keep abreast of them all and he was, on the whole, a great advocate of innovation in cricket and its coverage to maintain the public’s interest in the sport.

The news of Benaud’s death has generated an amazing response from around the world, with the Australian prime minister Tony Abbott calling him an “Australian icon” and promising a state funeral. Within the sport, Benaud imparted his knowledge with amazing charity, but in an understated way. This is probably why many cricketers, such as Shane Warne, have celebrated him as being an “absolute gentleman”.

While not strictly a pioneer of television sport, Benaud certainly became one of broadcasting’s most cherished and respected figures. His name will forever be synonymous with televised cricket for many millions of people in Australia and Britain.

Author

Richard Haynes